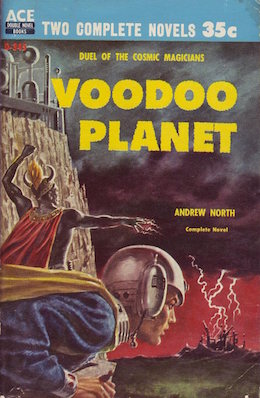

I’m a little sad that Voodoo Planet is the last of Norton’s Solar Queen novels. It’s quite short and feels like a coda after Sargasso of Space and Plague Ship—kind of “What We Did On Our Summer Vacation,” in between the wild ride from Sargol to Terra and the presumably uneventful postal run for which the ship is preparing when Captain Jellico and his very abbreviated crew are invited to take a quick break on a resort planet.

These books are so charming and so unabashedly all-in with the genre of the boy’s adventure. Zero girls, lots of excitement, and plenty of chances to get muddy and stay muddy.

This time the ship is just about ready for its postal run, with an obligatory frisson of anxiety about making deadline, and most of the crew is elsewhere. It’s only Jellico, Tau the Medic, and our protagonist Dane Thorson as Acting Cargo-master. Things are well enough under control that when one of the captain’s buddies shows up with an invitation to come over to the much more pleasant sister planet of the very hot, humid, nasty one they’re on, all three wait just long enough for the relief crew and then take off.

The planet Khatka is a safari planet, settled by African refugees from atomic war on Terra. (More on that in a bit.) It’s basically a huge hunting preserve for the very rich, and Free Traders aren’t nearly wealthy enough to book a vacation there—unless they’re invited by one of the planet’s aristocrats, Chief Ranger Asaki.

Asaki knows Jellico from his sideline as a xenobiologist. All Free Traders cultivate a hobby to while away the long, dull stretches between planets. Jellico studies alien life forms, Tau studies magic and superstition. Dane hasn’t quite settled on an avocation yet, but he fully expects to find one at some point. In the meantime he tags along and learns what he can learn.

It’s quickly apparent that Asaki has an ulterior motive for inviting the Free Traders to Khatka. A new game park is about to open, which is the lure, but there’s also political trouble: a witch doctor named Lumbrilo is harassing and undercutting Asaki. It also appears that poachers from offworld have been moving in on the preserve.

Very soon after Asaki and his guests land on the planet, they’re in trouble. First they have a confrontation with Lumbrilo, in which he and Tau come to virtual blows. Then they crash on the way to the preserve, brought down by powerful magnetic forces in a notoriously impenetrable swamp. Here for the first time in this series Norton seems to track on the fact that spaceships and air travel mean that planets can be surveyed from the air—though she immediately spikes it by making the area unsurveyable because of the above-mentioned magnetism. (She has not, though this novel was published post-Sputnik, extrapolated from air surveys to orbital satellites.)

Without a working aircraft, our heroes, including a native pilot who speaks in broken English, have to trek overland to the preserve and safety. Khatka turns out to be fairly completely hostile to human life, despite its pretty green vegetation. Everything, from the microfauna to the megafauna, is out to get them—as is Lumbrilo, who is in cahoots with the poachers, and who has pursued them with brain-bending magic and psychological terror.

But “primitive” magic is Tau’s area of expertise, and he manages to counteract Lumbrilo’s illusions with tricks and sleights of his own. In the end, Lumbrilo is abjectly defeated, the poachers are rounded up and arrested, and our heroes decide they’ve had enough vacation for one adventure. They head back to the Solar Queen and their nice uncomplicated postal route.

As nonstop as the action is and as charming as Dane and his crewmates are (Dane is an adorable dork who is quite competent at getting into and out of trouble), I still found this a very uncomfortable read. The title warned me that I might. Considering 1950s Norton’s overall issues with racial stereotyping, I saw “Voodoo” and, um. Yeah.

She is trying very, very, very hard to be what we now call diverse and inclusive. Her future is not uniformly white and mostly it’s not American (though Frank Mura the Japanese exile and Craig Tau the who-knows-what medic have terribly American first names). She takes direct aim at skin-color racism, in so many words, by creating a history in which a group of Africans survived Terra’s atomic holocaust, stole spaceships, and by pure luck happened onto Khatka.

There they bred for the darkest skin color possible, and over the centuries evolved an oligarchic culture that quickly figured out how to monetize itself and its planet. Our first sight of Asaki is of a very dark, barbarically splendid figure (very big, of course) who speaks perfect English (well, Basic) and is good buds with the equally tall Captain Jellico.

This is really trying to be radical and enlightened. People who think darker is superior, instead of paler. People who get along with other people regardless of skin color. A protagonist who up and says he doesn’t get why people care about color at all.

And yet it’s so much of its time, as we say around here. Naturally the African colonists are primitive and have witch doctors and turn their whole planet into a safari park. They’re very exotic and Other.

And of course it takes a white man to save the day. Tau isn’t labeled non-white, so one would presume that he isn’t; Norton is careful to let us know if someone is darker than the white norm, or if he has Asian or non-white features. As powerful as Lumbrilo is, Tau is more powerful. He out-witch-doctors Lumbrilo at every turn.

That’s the White Savior narrative, to go along with Primitive Savage Africa, generically labeled “Voodoo” (which it’s not; Vodoun is a specific ritual tradition), and the perpetual safari. Because Africa equals big-game hunting and superstitious natives.

Not only that, there’s a pretty big hole in the cast. Rip, the African-American crewman, is nowhere to be seen. You would think someone might at least mention that Khatka’s people are his distant relatives. Norton was never much for depth of characterization, so there’s no chance of a storyline in which Rip deals with the complexities of his own history and that of Khatka, but it seems a bit of a copout to disappear him from this of all installments in the Solar Queen‘s adventures.

By happenstance, I read this in the wake of the film Black Panther, which I have not yet seen, but I most definitely plan to. I have followed the comic for years, and I’ve kept up with the reporting on the film. And all I can think is, Norton did the best she knew how in 1959, but now it’s 2018 and we have Wakanda.

Wakanda in so many ways is the antithesis of (and antidote to) the “Voodoo Planet.” It’s proudly and thoroughly African, and it’s highly technologically advanced. The stereotyping of Khatka is painful in comparison.

And not just the “savage tribes are still pretty much savage despite better English among the elite” and “evil witch doctor is evil” tropes, either. Let us not forget the Dora Milaje, based in historical examples of women warriors. Here we get nothing but women who are locked up out of sight, and the universe is male, male, male.

I wouldn’t have known when I was a teen that this was a problem. Norton did her best to portray people who were not white, and built us a world in which they had resisted colonization and remained in control of their own territory. That’s pretty amazing for its time. But I’m not a teen anymore. I want—I expect—Wakanda.

So maybe Khatka, in its way, primed me for the real thing. I learned to see the future as something other than white, though this and the rest of the books in the series wouldn’t help me see it as anything but male. But now we have so much more.

I’ll tackle Star Hunter next, since it’s right next to the Solar Queen books on the shelf. We’ll see how that has held up over the decades.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her short novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published recently by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.

But it’s not: there was a follow-up by Norton alone, 1968’s Postmarked the Stars (which happens to be the first Solar Queen I read.). There were also three collaborative sequels:

Redline the Stars (1993) by Andre Norton and P. M. Griffin

Derelict for Trade (1997) by Andre Norton and Sherwood Smith

A Mind for Trade (1997) by Andre Norton and Sherwood Smith

I don’t know why extra blank lines are being inserted in this comment.

What Voodoo Planet might be is the only example of the crew of the Solar Queen actually managing to accomplish the goals of one of their contracts…

@1 Ooooo! (runs off to find these) Thank you!

James, you beat me to it. Postmarked the Stars is pretty hard to find but I was able to get it in epub form. It isn’t available for the Kindle that I’ve been able to find but I could read it on my Nook for the PC.

Redline the Stars is my favorite of the Solar Queen continuations that were written with Norton’s input but I like the “for Trade” books too and they are available on the Kindle.

Judith,

I just picked up and re-read Postmarked the Stars- I can mail it to you?

It’s a fun story, with interesting aliens.

Reviewer Tarr writes:

As opposed to, I guess, men in pith helmets hiking the territory, toting chains and theodolites on tripods and folding map tables.

I wonder why not? And how often, more generally, authors of the era (or any era) overlook implications that should be self-evident with a little extrapolation. Say, if you visualize yourself “I’m in a spaceship, high above the planet, watching the clouds and landforms below … hey, that hidden valley isn’t so hidden from this angle.” But if your writing-habit is character- or language-driven rather than scenery-driven, or if you’re doing a find-and-replace of adventure tropes (s/island/planet, s/boat/spaceship), maybe the possibility doesn’t even arise in your mind.

By analogy, “I’ve posited a new kind of interplanetary travel that uses another dimension, and its chief advantage is speed … But wait, why pass through orbit, as is customary? Why not just arrive inside a building on the planet’s surface?”

If I remember correctly, this is the book where every form of transport they try breaks down and strands them.

Judith,

Just so you and your readers know – Yes indeed the two books listed by James D. Nicoll (Derelict for Trade and Mind for Trade) are “Solar Queen” titles with a big but. The idea of teaming Andre and Sherwood together was the publishers not Andre’s. Andre and Sherwood did not get along and Andre was so frustrated by him that she walked away from both titles letting Sherwood write them. Upon reading them Andre declared them so bad that she had a friend named Paul remove them from her house in Florida and dispose of them. She would never discuss them or Sherwood after that. Upon her death the copyright was passed to Sherwood in hopes that they would never be associated with her Estate. To me they are actually very bad, and most fans of Andre’s work seem to agree.

Jay Watts – webmaster of Andre-Norton-Books.com

NOTE: the same goes for the other two titles with Sherwood’s name on them. (Atlantis Endgane and Echoes in Time – both from the “Time Traders” series)

@7 I don’t see what that information has to do with this discussion.

Sherwood is a she. Also, a friend. And my editor at Book View Cafe.

It’s a small world after all.

@6 Just the flitter, I think? But our heroes have frequent problems with transport.

@@.-@ Thank you so much! I ordered a copy before I saw your comment, but it’s lovely of you to offer.

Judith, have you changed your mind about the next book to be read? Will it be Postmarked instead of Star Hunter?

Interestingly, my copy of Voodoo Planet is the second half of a paperback containing Star Hunter!

@9 My copy won’t get here in time for me to read it, so we’ll stick with Star Hunter and then see if I have the book yet. My Ace Double has the abridged version of Beast Master on the other side. Interesting how they mixed and matched their selections.

I enjoyed Mind for Trade and Derelict for Trade quite a lot. They also let Ali and Mura get more time to shine and the book adds some actual aliens to the mix. And Dane grows up nicely without losing his charm.

*Edited to fix name spelling and to clarify that Mura is not the alien added to the crew.

**Also, more women join the crew.

As always, we ask that you keep the tone of your comments civil–rude, aggressive, or hostile comments directed at the author, moderators, or anyone taking part in this discussion will be unpublished. You can find the full Moderation Policy here.

Really hoping the Carolus Rex books will make it into the reread- if the co-authored bit doesnt chuck them from the running

I enjoyed the “…for Trade” books though not as much as I enjoyed Redline the Stars (I like disaster stories). I also enjoyed Atlantis Endgame. I’m surprised to hear that Norton didn’t like them, especially Endgame which I thought felt much like a Norton (though it obviously wasn’t written by her.

Towards the end of her life most of her books were co-written with other authors. I could usually see Norton’s influence but the books were obviously mostly written by the co-writers.

As for the current book, Voodoo Planet, it is my least favorite of the Solar Queen novels. I was always uncomfortable with the assumption that a planet colonized by blacks would choose such a primitive lifestyle. The emphasis on “magic” didn’t bother me so much. Many of her books had magic or psychic themes.

Sherwood Smith wrote about collaborating with Andre Norton on this very site.

I found all 4 of the books they worked on together enjoyable–and as a bonus, I discovered Sherwood Smith’s books.

@3 – there is a free software product called Calibre that will convert EPubs into the MOBI format that I believe can be read on Kindles.

If the EPUB has DRM applied to it, that needs to be dealt with before you can read the book on another device. There are Calibre add-ons that can help with that too (if you do some googling). Obviously such techniques should only be employed for accessing your book on different devices that you own, not distributing to others.

(I quite frequently buy from Amazon, but I convert my books to read on a Kobo, which I vastly prefer to Kindle. Also, Amazon can’t delete books off that device when they feel like it.)

Oh, and getting back (briefly) to the main topic, I read all of the Solar Queen books in public library collections in NZ, except this one. But I did find Postmarked the Stars.

There are some real vagaries in public library collections, but insert here my paen to their life-saving qualities. And while I’m thinking of that, and how threatened they are in three countries that I know of, I wonder if it’s necessary we “crowdfund” them. YES, they should be paid for out of municipal or state taxes. But since the fact is that they are increasingly not, and budgets are constantly cut, how do we ensure their survival?